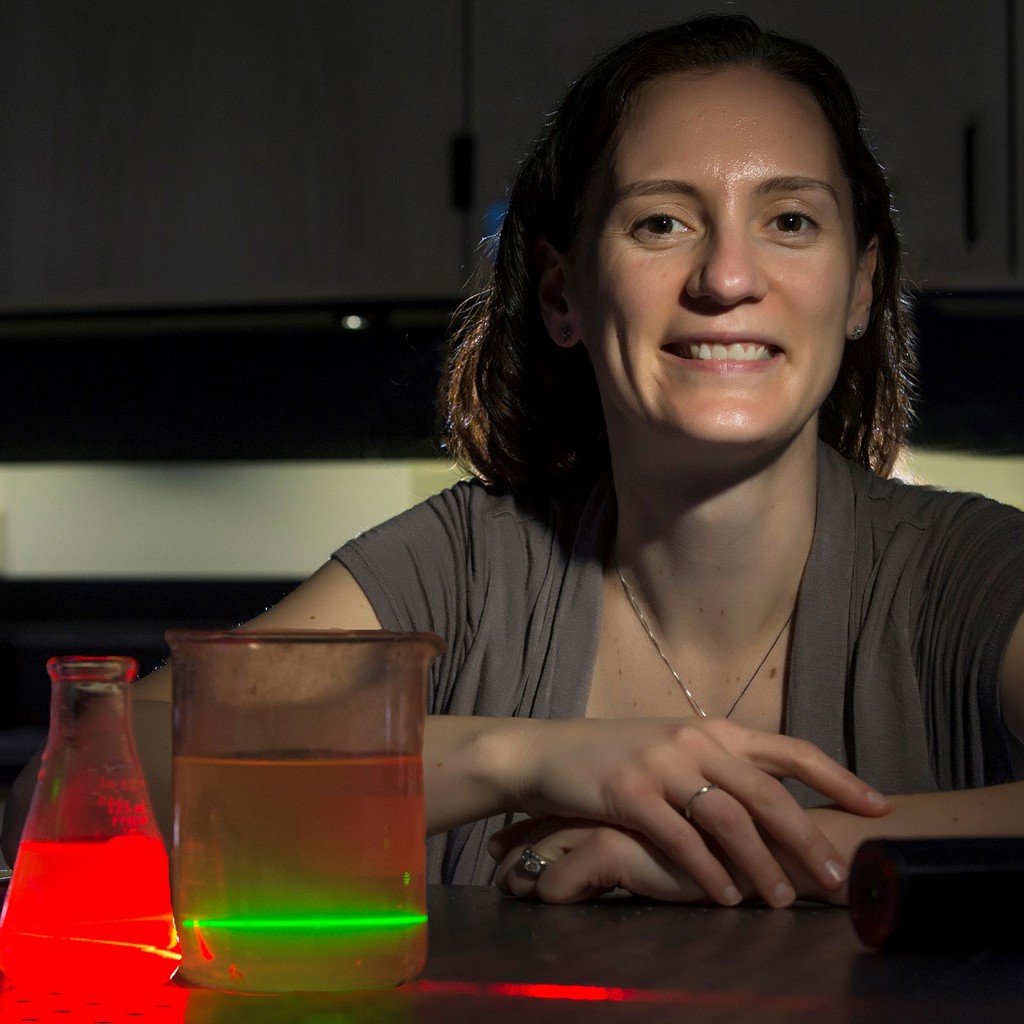

Melissa Skala

University of Wisconsin-Madison, USAFor innovation in the use of molecular imaging in cancer research and ophthalmology.

Melissa Skala wanted to be an astronaut. She loved to read about space, planets, stars, and light as a young person, and was curious, loved to learn, and most importantly loved to discover new things.” Physics was an easy fit in her early schooling. She says, “I loved physics because it answered a lot of ‘why’ questions. Why do we have gravity, why are there colors, why does a microwave heat up food? Discovery was exciting in physics.” During her undergraduate work, she was able to work in a biomedical optics lab one summer, and this is where everything clicked for her: “I had to ask around to find the right program and the right lab…but the work paid off as I found something that I still love to do.”

Today, she leads the Optical Microscopy in Medicine Lab at the Morgridge Institute for Research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and works to “discover new features of the immune system using photonics-based technologies that can monitor immune cell movement, function, and interactions in their native context.” Her work is getting a lot of recognition for its implications in cancer treatment, and is a truly exciting field. She comments, “The immune system is so complex and inter-connected that current tools have to destroy cells to understand them. It’s a messy web to disentangle, so this problem needs new technologies from physical scientists and engineers. There is a lot to learn, and I find that motivating.”

Her lab is currently working on new ways of determining the best treatments for cancer patients: “My lab uses photonics-based technologies to develop personalized treatment plans for cancer patients (including breast, pancreatic, colorectal, neuroendocrine, oral, and other cancers).” She works closely with oncologists to collect fresh biopsies from patients, which are then maintained in a 3-D culture. These cultures can be used to test the response to different treatment options, which helps get to the right treatment for each patient faster. Her lab does this by using autofluorescence, and she comments, “The great thing about autofluorescence is that it's free information, we don't have to kill the sample or add contrast agents to learn about the state of the cell. We can carefully collect this weak fluorescence, and time its arrival, to understand how a patient will respond to treatment options. This enables unique measurements of single cell response on patient samples, which could inform cancer drug development and treatment planning in the clinic.”

As exciting as her current work is, it was not an easy journey to get there. “I failed a lot with experiments,” she says, “looked at a lot of rejection letters, but always found a way to learn from failure.” She goes on to say, “Failure is a great motivator and a great teacher, and now I know that there is success and learning, rather that success and failure.” An important distinction to make for all people in all disciplines, from research to business to the arts. Embracing the challenge and adversity is the only way to move forward. Throughout this all, she had mentors to help guide her. “I chose mentors who had a similar curiosity and love for science. They were important to me because they kept me going when I was discouraged, they taught me how to communicate, design experiments, ask questions, ensure rigor.” She encourages all young scientists to choose the right mentor for them. She says it is the most important part.

Looking back on her career, Melissa offers some words of advice to young people starting out in her field: “try to gain as much exposure as possible.” She shares that she grew up in a small, rural town, and only had books from which to learn. College afforded her the opportunity to meet people, work in a lab, attend seminars, and learn from her professors. “Surround yourself with supportive people, and do what you love.” Melissa talks about how OSA has helped her grow her network of support: “OSA conferences have been critical to my growth as a scientist, from networking opportunities to leadership experience and building good communication skills. The OSA community supports trainees, and that’s why it’s such an important society.”

Photo Credit: Vanderbilt University

Profile written by Samantha Hornback