What Doesn't Kill Me

About Optica

09 August 2022

What Doesn't Kill Me

How a fascination for light helped a young quantum physicist survive war-torn Iran and find belonging among an international community of scientists.

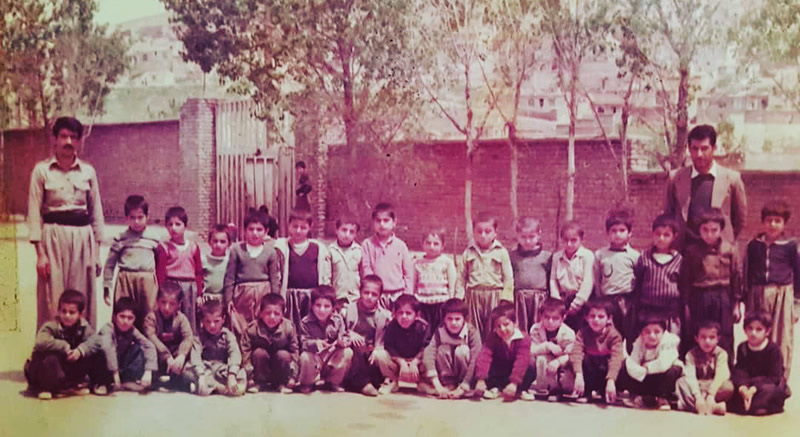

On a sunny day in 1987, a young Ebrahim Karimi sat in his fourth-grade class gazing out of his school window like any other ten-year-old boy. Looking up to the sky, he saw beautiful glowing orbs of light and marveled at the pretty colors and shapes they started making. Were these hundreds of mirrors falling, or were they giant fireflies? His wonder was cut short: they were bombs heading straight for his city. His class jumped out of their chairs and abandoned their textbooks to save themselves. Young Karimi stared up at the luminous objects in awe. He was now forever enthralled with light.

All Karimi wanted to do was learn, but being a Kurd in Iran in the late 80s meant this would not happen easily. Widely acknowledged as the biggest ethnic minority in the world, the Kurds are a nation without a state, a people with no country of their own. Spread throughout Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey, the Kurds have a history of persecution and conflict in these ‘host’ countries. To make matters worse for young Ebrahim, he was from a political family whose beliefs opposed the new regime. “I was born a few months before the Revolution, and my family played an active political role contrary to the new theocratic regime."

This uprising was the Islamic Revolution in 1978-79 that replaced a pro-Western absolute monarchy with an anti-Western theocracy and led to an Islamic republic in Iran. “My father and uncle were Democrat politicians who supported the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan. Before the Revolution, these were legitimate jobs as politicians at the time of Shah—the last Shah of the Imperial State of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. This was when all members of opposing political parties were welcome to join and have communal discourse and discussion. It was a relatively peaceful time, but then life changed quickly.”

The regime change was as fast as it was brutal. After the election of the Ayatollah (Ruhollah Khomeini, Iran’s first supreme leader), new government forces targeted people like his father and uncles. “My two uncles were killed, one executed in the city, the other dying in the conflict. Then, I learned my father had been arrested and faced the death penalty." Karimi's grandfather pleaded for mercy with the Deputy of the Ayatollah, who then reduced his sentence from death to 15 years in prison. "It seemed like many lifetimes, but he would be released after almost eight years." This was a great relief for young Ebrahim and his family, but many of his troubles still lay ahead.

With his mother, brother and aunts, Karimi fled to his grandparents’ home in the Iranian countryside, deep in the snow-capped mountains. Karimi went from a prosperous life with a politician father to living in absolute poverty by today's standards. Stuck in the cold mountains, he had no electricity, central heating or running water. Karimi could be forgiven for resenting his new life. Instead, he accepted these circumstances and thrived, losing himself in science books and teaching himself calculus by age twelve. “It was an enforced home-schooling, but I loved it. We might have had little material wealth, but there was so much beautiful nature around me. We were incredibly rich in inspiration.” Karimi flourished, learning about science and optics from the natural phenomena around him. "Every morning, light waves caught the river, and at night we saw lunar halos. It was paradise for a budding optical scientist, even if we were sandwiched in a war zone.

"Every morning, light waves caught the river, and at night we saw lunar halos. It was paradise for a budding optical scientist, even if we were sandwiched in a war zone."

The Karimi family stayed in this haven until it was safe enough for Ebrahim to enroll in a secondary school nearby. School was challenging for the young Kurdish Iranian, who was academically more advanced than his classmates. "As Kurds, we did not have the right to read, write and speak in Kurdish, our mother tongue. Even though I was never interested in politics, for someone like me with ties to a political family, it was virtually impossible to be accepted in a government-funded institution.” But Karimi got lucky. “The year I applied to university, President Khatami was elected, ushering in a much more tolerant and diplomatic era. He opened up discourse with opposition groups, which I feel played a huge part in my getting to university." Starting his studies was not straightforward.

Once enrolled at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Basic Sciences, Zanjan, Iran, Karimi found it difficult to secure a simple student ID card. "It was like joining the secret service. Official guards paid my grandfather a visit. They interviewed him and neighbours to see if they thought I would cause trouble. After this, I had to get permission to study." He had to go to Tehran for security clearance to get his student ID card. "I arrived at the security office, which looked like something from an old Soviet Union movie. It was ugly, and they had a guard at the front."

After keeping him waiting for two hours, a soft-spoken, polite gentleman came and took him to a large, dark room. “It's such a cliché, but I had to sit in the middle of the room. Two officials sat about twenty feet opposite me, behind the polite man who collected me. They said nothing to me but whispered to each other. I was told they couldn’t find anything about me in my file. I didn’t even know I had a file! They went through everything about my family and who my uncles were. Then they brought up my father's past. I thought, my career has ended before it’s even begun." The officials asked him to declare that he would not conduct any political activities or cause trouble. "I told them I'm a scientist and not interested in politics. I love being at your university. Then I signed an official pledge which they added to my file." A few weeks later, the ID card arrived.

Following his graduation from Zanjan, he was accepted for a PhD at two overseas universities—the University of Queensland, Australia and Vrije University, Amsterdam. Despite having all his documents, such as an enrolment form, an acceptance letter and his tuition fee schedule, he was denied leave by the Iranian government. “My father said go and escape Iran as a refugee. I said no, I want to come back and visit you whenever I want. So I had to complete military service.” Far from being a chore, he spent his three years of conscription in a civilian role teaching at the University of Kurdistan, a role he loved and an environment in which he thrived. “A friend from Zanjan said, instead of military service, why not do public service? So, I got my first role as a lecturer in 2004. It was amazing. I didn't face any discrimination. For the first time in my life, my ethnic and political identity didn't matter. More importantly, I met my lovely wife, Rahil Golipoor, who has been a great advisor and supporter to me."

"For the first time in my life, my ethnic and political identity didn't matter."

When his involuntary draft ended, his two PhD offers had expired. Starting over again, he was accepted into a fundamental and applied physics course at the University of Naples, Italy, where he also took a post-doctoral fellowship. It was his move to Canada where his career started to blossom. “Though I moved to Canada, I became an adjunct professor at Zanjan. I became a fellow at the National Research Council Canada and a visiting professor at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Light.” At Max Planck, he and his colleagues made their first ground-breaking collaboration, a Möbius strip—a shape made by snipping a paper ring, adding a twist, and then joining the ends together again—made entirely from light. “Making the structured-light Möbius was equally as joyous as studying calculus aged twelve. I felt that same delight. It was extraordinary.”

When he became a professor at the University of Ottawa in 2015, Karimi’s career was in full flow, but not for the first time, he found himself displaced. Unable to return to his family in Iran for some time, Karimi was without a home or country. He found a new sense of belonging when he became part of a unique "family" of scientists who all speak the universal language of science and mathematics. Where he was once treated with suspicion and shunned, this new community gave him acceptance and welcome. Karimi credits the moment he felt truly part of the community to his time staying with the renowned theoretical physicist Sir Michael Berry, who developed the Berry Phase, a property of waves in quantum mechanics. “Sir Michael became a great mentor to me. In 2017, I stayed with him as we went from conference to conference. I had not seen or spoken to my family back home for such a long time, and then it hit me—I realized Optica had become my family and home. This 'family' of scientists had given me the strength and stability to succeed while away from my homeland. As scientists, we have all the same worries, concerns and goals. We are pushing the borders of science and technology. And we want to bring science to every corner of the world.”

"This 'family' of scientists had given me the strength and stability to succeed while away from my homeland."

A natural optimist, Karimi did not allow any negative experiences to affect his well-being or outlook. "Every bad thing that happened, I took something from it. There are no problems in life, only tasks. You miss the train, okay, let's get the next one. I have no papers, let's find a way to get some. It has made me grateful for what I have today. To quote Nietzsche, 'what doesn't kill me makes me stronger.' Sometimes you have to wonder what could have been, but it is what it is. You have to be in the right place at the right time.”

Karimi's life is very different today from his early years in Iran, but he still has the same fascination with light and how it behaves. Ebrahim Karimi, 45, is now one of the world’s most eminent quantum scientists. Group leader of Structural Quantum Optics at the University of Ottawa and co-director of Nexus for Quantum Technologies, Karimi holds the Canada Research Chair in Structured Quantum Waves. He was also elected as an Optica Fellow in 2019. His work on "structured quantum waves" is a revolutionary new way of thinking about how light behaves at the atomic level.

The Optica Community unites a diverse, global population of students, scientists, engineers and professionals. We invite everyone in our community to forge the connections vital to solving societal challenges through light science and technology.

Media Contact